|

Related Pages: |

The Lone Eagle, Charles Augustus Lindbergh. In 1927 Lindbergh's solo

trans-Atlantic flight stunned the world and turned him into an overnight hero.

Two years before the Depression struck, Lindbergh seemed to epitomize the very

essence of an ebullient America that never looked back. His lanky good looks,

nicely muted by a shy, almost diffident smile, proved the perfect foil to a deed

of enormous courage. The U.S. bowed happily before its new hero, " Lucky Lindy.

" With fame and hard work, Lindbergh prospered. His marriage to Anne Morrow,

daughter of distinguished statesman and diplomat Dwight W. Morrow, proved long

and abiding. His fortunes multiplied, as did his family, when Anne bore their

first son on 22 June 1930, her birthday. Novelist E Scott Fitzgerald wrote:

"Show me a hero and I will write you a tragedy. " On the night of I March 1932,

the Lindbergh’s’ child, lovingly called "Fat Lamb" by Anne and "Buster" by

Charles, was kidnapped and murdered. The weeks of anguish which followed

embittered Lindbergh, heightened by the intrusions of the press and hideous

crank calls that mocked his grieving. Nothing quenched Charles' disappointment -

in America and its people. On 7 December 1935 he made a decision, telling Anne

to pack and be ready to leave on a day's notice. They would abandon the U.S.

Fifteen days later the two set sail for England. Lindbergh's dalliance with Europe forever changed his life. An earlier

acquaintance and distinguished British civil servant, Harold Nicholson, offered

Charles and Anne the use of Long Barn Cottage, near Nicholson's castle at

Sissinghurst in southeastern England. At that place the Lindbergh's rebuilt their

lives in the solitude of the Kentish countryside; from that place Lindbergh

ventured out into a changing world. Over the next few years he became acquainted with a number of people but it

was through the Army Air Corps' singular attaché in Berlin, Major Truman Smith,

that Lindbergh went to Nazi Germany. He accepted an invitation from the Nazi

Government, initiated and forwarded by Smith, to visit Berlin. Once there,

German officialdom threw down the red carpet and dazzled Lindbergh. The Lone

Eagle came away from that trip with a changed perspective. At heart Lindbergh had one serious flaw. An honest man, he believed people

returned that honesty. That others lied, the man found hard to accept; that a

government lied was beyond his comprehension. His tour had been carefully

staged; unseen were the political camps and obvious anti-Semitic demonstrations.

Instead Lindbergh saw a dynamic Germany churning out "defensive weapons,"

awesome in numbers and quality. The epicenter of his crises, however, devolved on a simple fact - Lindbergh

feared for the U. S. How could the Depression-crippled nation he left behind

compete with the material and moral superiority of a resurgent Germany? Lindbergh returned home in the

spring of 1939. But he had seen and understood too much to remain silent any

longer. So the Lone Eagle set in motion events that would eventually see him fly

with Satan's Angels’. In the years following his return, Lindbergh slowly alienated himself from

the Administration and the American people. He joined one of the strongest

Noninterventionist groups, the American First Committee, in April 1941, and

became a major figure in its campaign to keep the U.S. neutral. The crunch came

with a series of radio talks in which Lindbergh warned against supporting the

Allies because of a perceived German conquest of Europe. His stature among

Americans was seen as a powerful counterweight to FDR.'s attempt to support the

Allies " short of war. "

On 29 April 1941, two days after Roosevelt impugned his loyalty in a speech,

Lindbergh resigned his colonelcy in the Air Corps Reserve. Public reaction that

once idolized him, was no longer sympathetic.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor sank both ships and isolationist aspirations. It placed Lindbergh in a quandary but in a patriotic spirit he offered to aid the U.S. by returning to the Air Corps. It was too late. The Administration refused his services and then, in a mean spirited mood, forced Lindbergh's many aviation employers to cancel his advisory positions, including Juan Trippes' Pan American Airways. Only one man resisted that move, Henry Ford, and Lindbergh went to work for him on 3 April 1942 as a technical consultant helping Ford convert from auto to bomber production.

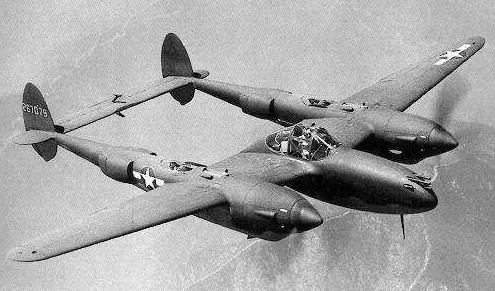

Over the next year Washington loosened a bit. Lindbergh's undeniable expertise with aircraft and pilots thawed the bans against him. Indeed, his diary shows an enormously busy schedule of test flights that solved pressing problems of new aircraft. In that process the Lone Eagle flew, and came to know well, almost every combat craft in the U.S. inventory. But Lindbergh hungered for combat and as early as January 1944 had made inquiries as to that possibility. The Marines responded first. Cautiously, a tour of Corsair bases in the Pacific was arranged.

In April a friendly U-S- Navy sanctioned and covered Lindbergh's trip. He would go to their theater, the Pacific, as a civilian technical assistant. Neither the White House nor even Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox knew of this trip. After kitting up with Navy uniforms from Brook; Brothers (sans any insignia) and taking the usual rounds of shots, Lindbergh left San Diego for the War Zone.

By March he had already regularly contacted the United Aircraft Corporation, producer of the F4U Corsair, and had agreed to act as its liaison in the field. Once situated at Guadalcanal, South Pacific Area, he corrected problems of the "bent-winged bird" established better communications between United Aircraft and the Marines. There, local Marine officers consented to take Lindbergh on a patrol to Rabaul, the first of fourteen combat missions he would fly with the Corps. With the exception of air-to-air combat, Lindbergh flew patrol, escort, strafing, and dive-bombing assignments- As would later occur with the Army Air Forces, officers winked at his extraordinary activities by according him "observer status." Lindbergh concluded his business on the Canal. By 15 June he landed at Finschafen bound for the 475th Fighter Group.

|

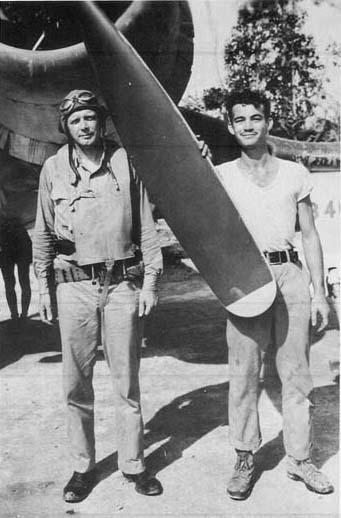

He announced his presence to V Fighter Command at Nadzab. -Colonel Merian C. Cooper lunched with Lindbergh and on Sunday. evening, 18 June, the civilian dined with Whitehead, talking of New Guinea developments and, doubtless, Lindbergh’s plans. This proved later insufficient for proper authorization in the theater. On Tuesday he got in an hour and twenty minutes Lightning time with 35th Squadron, 8th Group. A week later Lindbergh flew to Hollandia and walked in on MacDonald and Smith's checker game.

After obtaining permission to accompany the group on the next day's mission, Lindbergh retreated to V Fighter Command Headquarters only to be retrieved later by MacDonald. The mission, explained the colonel, would launch at dawn. It would be better to rest at the 475th camp and cut down transportation problems. Lindbergh agreed.

Meanwhile the "word" spread quickly. Lindbergh was among Satan's Angels. In the 433rd camp, First Lieutenant Carroll R. "Andy" Anderson tried to summon up enough strength to write a long overdue letter to his wife, Virginia Marie. Suddenly friend C.J. Rieman popped in and announced, "Charles A. Lindbergh is going to fly with us!" Letters were quickly forgotten.

The next day's mission was to Jefman Island, now a familiar target for the 475th. With the possibility of interception much higher than on Guadalcanal flights, MacDonald took no chances. The four-craft patrol included some of the best pilots in the group: MacDonald, with Smith in the number two slot, followed by Lindbergh and his wingman Mac McGuire. By that flight the veterans already had a total of thirty-six victories between them.

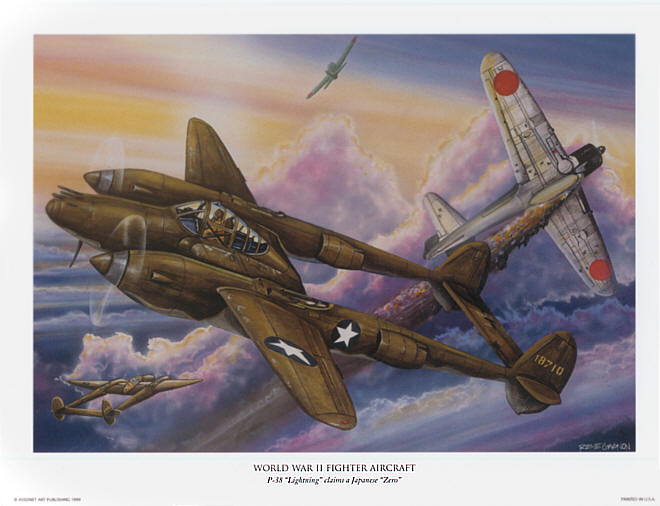

Except for flak, Jefman produced no action and so, as had been the recent practice, the quartet of Lightnings shot up barges and luggers on the way home. The Japanese used the terrain to mask their boats from air strikes. Spotting a barge in an indentation formed by two hills leading to the sea, Lindbergh flew up and over the nearest ridge clearing the top by a dozen feet, shooting as he partially straightened, and then banked hard left to clear the opposing hill, all this at 250 miles per hour indicated air speed. The four Lightnings left several craft sinking or burning before turning for home.

Later the group approved of Lindbergh is handling of that first mission. Intelligence Officer Dennis G. "Coop" Cooper was impressed by his accurate and thorough observations during debriefing. He flew well and low against the targets. They did not realize that Lindbergh's time on Guadalcanal had already honed his combat skills.

.A number of his missions in F4Us involved strafing difficult targets. In that process, he learned to fire accurately no matter what his fighter's attitude. " I do not think about the plane's position; that is taken care of subconsciously. All my conscious attention is concentrated on the sight. The tracers are going home, that's all that matters. " Further, Lindbergh was a natural marksman. He shot trap and skeet and while on a PT boat speeding at 26 knots, shot a flying fish with his .45 automatic Before going overseas he practiced air-to-air gunnery at El Toro, California, and Hickam Field, Hawaii, and his time at Guadalcanal allowed him to fire guns in action. Lindbergh's modesty kept him silent about his skills.

Lieutenant John E. "Jack" Purdy of the 433rd looked forward to meeting Lindbergh. Eventually a seven-victory ace, Purdy brooked no formality; already it was "Charlie." Almost as if sensing the stir caused by Lindbergh's appearance, MacDonald called a meeting two days after Lindbergh's arrival. The 475th's C.O. sought to clarify the civilian's status among Satan's Angels. The Lone Eagle would be accorded all officer's privileges and would be addressed as "Mister Lindbergh" as befitting his non-military status.

The Lone Eagle sortied regularly with the 475th and the missions reveal two things only partially seen by the group itself. The first concerned changing roles. Japanese resources dwindled at this, the closing of the New Guinea campaigns. Now they faced the terrible mobility of Nimitz's Central Pacific carrier task forces while MacArthur primed for the drive north against the Philippines) Gone were the relentless daylight air attacks. Husbanding resources in the Southwest Pacific, the enemy took to nocturnal raids against targets like newly-invaded Biak. Until MacArthur moved against the Philippines, the 475th provided aerial protection but did little damage to Japanese resources. This was unacceptable to Charles MacDonald.

Satan's Angels' C.O. began ordering strafing missions on the homeward leg of all patrols. Andy Anderson of Possum Squadron explained that the skipper was "a real bear for getting his money's worth on every mission. " Thus the recent spate of strafing attacks like the one that concluded Lindbergh's first outing with the 475th.

On the mission slated for 30 June, his second, the Lone Eagle took part in another of the many tactical transformations the group witnessed in recent months. With nil aerial opposition the group carried 1,000-pound bombs to Noemfoor Island. They would continue to carry "freight" for the rest of the war and Lindbergh accompanied them on this second such attack.

The seventeen ships lifted off the mat strip, flying through broken clouds and out to sea by 1125. Over the target they circled, waiting for the A-20s to complete their runs, watching them crater the revetment area down the entire side of the enemy runway. The resultant smoke cleared and the 475th began its attack. Lindbergh, the only one who had recent dive-bombing experience, rolled off at the edge of a squall, steadied his Lightning, and "pickled off" his weapon at 2,500 feet. He pulled out of the dive before the ten-second delayed bomb touched off.

Later the group's Official History recorded all bombs were delivered with "fair accuracy." Lindbergh saw part of the subsequent attacks and noted "three bombs in the target area, two in the jungle, and three in the ocean." Experience, however, would make the 475th as proficient with bombs as they were with bullets.

The second and critical passage made by the group concerned fuel consumption. With additional fuel cells in the J model P-38, Satan's Angels had been making six and one-half and seven-hour flights. On I July Lindbergh flew a third mission with the group, an armed reconnaissance to enemy strips at Nabire, Sagan One and Two, Otawiri, and Ransiki, all on the western shore of Geelvink Bay. Already Lindbergh's technical eye noticed something. After six and one-half hours flying time, he landed with 210 gallons of fuel remaining in his Lightning's tanks.

Two missions later, on 3 July, the group covered sixteen heavies on a strike against Jefman Island. Lindbergh led Hades Squadron's White Flight as they wove back and forth above the lumbering B-25s. After the attack the Lightnings went barge hunting.

First one, then two pilots reported dwindling fuel and broke off for home. MacDonald ordered the squadron back but because Lindbergh had nursed his fuel, he asked for and received permission to continue the hunt with his wingman. After a few more strafing runs, Lindbergh noticed the other Lightning circling overhead. Nervously the pilot told Lindbergh that he had only 175 gallons of fuel left. The civilian told him to reduce engine rpms, lean out his fuel mixture, and throttle back. When they landed, the 431st driver had seventy gallons left, Lindbergh had 260. They had started the mission with equal amounts of gas.

|

Lindbergh talked with MacDonald. The colonel then asked the group's pilots to assemble at the recreation hall that evening. The hall was that in name only, packed dirt floors staring up at a palm thatched roof, one ping pong table and some decks of cards completing the decor. Under the glare of unshaded bulbs, MacDonald got down to business. "Mr. Lindbergh" wanted to explain how to gain more range from the P-38s. In a pleasant manner Lindbergh explained cruise control techniques he had worked out for the Lightnings: reduce the standard 2,200 rpm to 1,600, set fuel mixtures to "auto-lean," and slightly increase manifold pressures. This, Lindbergh predicted, would stretch the Lightning's radius by 400 hundred miles, a nine-hour flight. When he concluded his talk half an hour later, the room was silent.

The men mulled over several thoughts in the wake of their guest's presentation. The notion of a nine-hour flight literally did not sit well with them, "bum-busters" thought some. Seven hours in a cramped Lightning cockpit, sitting on a parachute, an emergency raft, and an oar was bad, nine hours was inconceivable. They were right. Later, on 14 October 1944, a 432nd pilot celebrated his twenty-fourth birthday with an eight-hour escort to Balikpapan, Borneo. On touching down, he was so cramped his crew chief had to climb up and help him get out of the cockpit.

The group’s chief concern surfaced quickly, that such procedures would foul sparkplugs and scorch cylinders. Lindbergh methodically gave the answer. The Lightning's technical manual provided all the figures necessary to prove his point; they had been there all along. Nonetheless the 475th remained skeptical. A single factor scotched their reticence.

During their brief encounter, MacDonald had come to respect Lindbergh. Both men pushed hard and had achieved. Both were perfectionists never leaving things half done. And both had inquisitive minds. John Loisel, commanding officer the 432nd, remembered the two men talking for long periods over a multitude of topics beyond aviation. If, as MacDonald had informed his pilots, better aircraft performance meant a shorter war, then increasing the Lightning's range was worth investigating. Lindbergh provided the idea, but it was MacDonald's endorsement, backed by the enormous respect accorded him by the group, that saw the experiment to fruition. The next day, the Fourth of July, Lindbergh accompanied the 433rd on a six-hour, forty-minute flight led by Captain "Parky" Parkansky. Upon landing, the lowest fuel level recorded was 160 gallons. In his journal entry Lindbergh felt ". . . that the talk last night was worthwhile. " The 475th had lengthened its stride.

On 7 July Lindbergh flew back to Nadzab. The 475th continued its tasks but began to incorporate the lessons taught by the departed aviator. But it was not the end of their association. They would meet again on the road to the Philippines, a road that MacArthur had long been anxious to travel.

MacArthur's clean-up of Eastern New Guinea took fifteen months. With supplies, experience, and proper tactics, he had leaped the top of the Guineas west to Vogelkop and then north to the Moluccas in three months. On 15 September MacArthur looked north from Morotai. He was only three hundred miles from the Philippines; it could have been the moon.

Pacific plans still remained unjelled. Ironically this time the culprit was success. The success that saw MacArthur's seizure of New Guinea also sent Nimitz rampaging through the Pacific islands. On 26 July 1944 MacArthur and Nimitz met with President Roosevelt at Pearl Harbor. FDR explained that Washington planners felt encouraged to scrap the year-old "Strategic Plan for the Defeat of Japan." This guideline posited the securing of China's southern coast, Formosa, and Luzon as a prerequisite to striking the Home Islands. Now Washington boldly sought direct attacks against Formosa, or Japan itself, thus bypassing Luzon. The ensuing conversation was lively.

Nimitz generally conceded the need for long-range aircover in any attempt at taking Formosa. In a long exegesis, MacArthur pointed out the moral imperative: freeing the gallant Filipino people and expunging a defeat of American arms; his defeat, the general might have added. In an earlier message JCS head George C. Marshall reminded MacArthur that "personal feelings and Philippine politics" should not cloud over the war's prime objective, to defeat Japan. To MacArthur they were one and inseparable. FDR reacted to those lofty sentiments by taking an aspirin . . . and ordering another for the morning. Nonetheless the meeting's end saw FDR agree to support the two commanders and push for an invasion of the Philippines.

For the 475th, those were great - but distant - events. Life for them still revolved around coral, seas, and sky. Lindbergh's departure made no dent in the 475th's regiment. On 2 July 1944 the Allies strengthened their grip on routes to the Philippines by attacking Noemfoor, most westerly of the Schouten Island group. Lightnings from the group covered that landing as well as those at Sansapor, the northwestern-most part of New Guinea on the thirtieth of the month. By then Satan's Angels had moved again.

Biak Island highlighted a continual problem for Southwestern Pacific campaigns. The heart of that dilemma involved Allied dependence on captured Japanese airstrips. Japanese-engineered runways lacked the polish of their American counterparts. The lighter enemy craft could employ runway surfaces that were thinner, their lengths shorter. U. S. fighters had difficulty enough, but steel matting helped convert them to American specifications. The real problem revolved around the heavies, B-24s and -17s. The enemy had no such massive craft and so heavy bomber runway facilities were hardest to develop. The many moves completed by Satan's Angels stemmed as much from airfields proved inadequate as from the rapid progress of the war. Cape Gloucester, Finschafen, and Hollandia evicted the 475th. Biak now beckoned.

Located 275 miles west of Hollandia, Biak had been attacked by the 41st Division on 27 May 1944. Local defense commander Colonel Naoyuki Kuzume had learned that Japanese troops on the waterline inevitably died or could not retreat under pre-invasion bombardments. He pulled his men back into coral catacombs dotting the landscape. The ensuing struggle for the island was one of the worst of the war. Even as the Seabees and engineers reconditioned strips at Owi Island, just off Biak, and then on Biak itself, Japanese snipers and suicide teams kept the area a combat zone. Some of the enemy held out for months. The 475th again lodged hard on the edge of battle.

On 10 July the air echelon landed on Mokmer Strip, Biak. Two men were missing. Crew chief Sergeant Teddy Hanks, swinging aboard the last C-47 transporting the air echelon to Biak, noticed a 38 limping back to land, snafued. With no mechanics left, Hanks and fellow Sergeant George A. Brown dismounted. Brown had repaired airplanes before the war and was one of the few men that came to the 475th with prior experience. Together they repaired the Lightning, telling the pilot to buzz them on the way out. Happy to oblige, the pilot roared in so low that a terrified earth-mover operator bailed out onto the ground. The entire group completed the move four days later.

Mokmer strip had been chiseled out of a hillside overlooking the beach and sea. The runway was white, compacted coral with good drainage in rain and dusty in the heat. The temporary camp lay at the eastern end of the strip. The later "permanent" encampment at Sorido would be a mile and a half from Mokmer, connected by a bumpy road. Both sites spread out over the same crushed coral as the strip, road, and island. Early on, Tokyo Rose acknowledged the 475th's presence as the "Butchers of Rabaul" and promised a nasty welcome. A 432nd pilot later explained, "It's hell trying to dig a foxhole in coral."

|

General camp conditions were decent by earlier standards. While hot, the tradewinds cooled things off in the evening and the ocean always beckoned for a swim. Showers were available, and while the food improved little, one could always scrounge survival, " melt-proof" chocolate bars from the parachute riggers who seemed to have an endless supply. Liquor remained habitually scarce. Yardbird Lieutenant Lloyd C. Lentz, Jr., 431st Squadron, solved the problem in style. His wife sent him Scotch or bourbon in medicinal containers. On scattered Pacific atolls "are empty Listerine bottles in island trash heaps," mute testimony to American ingenuity and the demand for a decent drink.

A welcomed addition arrived in the Satan's Angels' revetment, a B-25 Mitchell. Late of the 345th Bomb Group, it had flown its share of missions and now served to make "Fat Cat" runs to Australia. A silvery ship with a solid metal nose, the Mitchell bore the title "Fertile Myrtle, " a name straitlaced Lindbergh found objectionable. On its maiden voyage, officers and men kicked in money for supplies and especially fresh produce, milk, and meat. Much to the disappointment of the EM'S, "Myrtle" returned with liquor, most of which went to officers' country. Later flights were more equitably divided. Unfortunately even with fresh provisions, their proper preparation was still occasionally lacking. Private First Class Curtis E Tinker, Jr., of the 432nd Squadron, recalled that the cooks, upon receiving a shipment of fresh eggs from a "Fat Cat" flight, promptly fried them in Australian mutton tallow.

Air engagements grew increasingly rare as the Japanese girded for the forthcoming struggle for the Philippines. Except for victories in the first four days of July, the group waited out a drought in air fighting. By the end of the month circumstances changed.

On 16 July Lindbergh returned to the group. Earlier Kenney had called him back to Brisbane, the civilian arriving by 21 July. Apparently the problem stemmed from miscommunications, protocol, and a genuine concern for the Lone Eagle's safety. Conversation brought agreement and much like Marine Corps officialdom on the Canal, Lindbergh received " observer-status" and permission to use his guns in self-defense because, as Kenney told him, ". . , no one back in the States will know whether you use your guns or not. Officially sanctioned, he returned to the 475th.

Lindbergh easily re-entered the flow of group activities. Despite the mandated "Mr. Lindbergh" title, the officers and men accepted the former Air Corps colonel as well as any outsider could expect. They kidded him, carefully measuring Lindbergh's response and never finding him wanting.

Good humor, in fact, was necessary because flying combat missions had not made him a combat pilot. After one takeoff, Lindbergh noticed he lagged behind the 433rd despite his best efforts to catch up. A pilot quipped over the radio, "Get your wheels up! You're not flying the Spirit of St. Louis. " Lindbergh had forgotten to retract his landing gear. Other incidents had less humor but were met with the same unfailing grace.

Possum Squadron, the 433rd, owned and groomed an idiosyncratic reputation, They did nothing by half measures. Major "Louie" Lewis insisted on sharp flying, often bringing the squadron over a runway in precision order, each fighter trailing ribbons of condensation from wingtips as they peeled off to land. Lindbergh received a rude introduction into the intricacies of squadron styles while flying with the 433rd. Lewis employed a rapid two-craft takeoff, the entire squadron expected to be emplaced within a single circuit of the field. Sound reasoning backed his method. Long takeoffs and assemblies meant less gas in flight, often spelling the difference between success and failure over the target or life and death on the long trip home. On one such mission Lewis looked back to see a lone P-38 on the strip, Lindbergh's. After the squadron completed a number of circuits the Lightning ambled off the runway, made a leisurely ascent, and joined up with the now fretful Possums. Later Lewis explained how the squadron operated and Lindbergh promised to preflight before the 433rd assembled and to "pull streamers" on takeoff. The Lone Eagle was learning.

|

In support of the Sansapor invasion, a raid had been slated for the next day but bad weather delayed the mission until 27 July At 0745 the group lifted off to escort the first U. S. strike on Halmahera, one of two major islands in the Molucca Group, air "Intel" estimating 150 aircraft scattered over three fields, 75 to 100 probably fighters. With the 431th Lindbergh flew close cover to the B-25 strafers, the other squadrons flying at intermediate and high altitudes.

Now fully aware of radar's ability, the battle group traced the sea at 2,000 feet staving off their presence on Japanese plotting boards for as long a; possible. Halmahera's hazy purple coastline appeared, then cleared to white sand beaches and verdant jungles. High cover rose above the group and the 475th broke into its combat strings that wove protectively above the forty gunships. The sweep into Galela strip, their target, took them past an active volcano, its sulfurous fume; invading cockpits, ashen smoke reducing visibility to a minimum. As the leading wave of B-25s smothered Galela in a wash of tracers and parafrags, Lindbergh and the 433rd rose and circled the drome watching the second line of Mitchell's do their work before escorting the third echelon of strafers out to sea. In their wake the Fifth left sixty smoldering Japanese craft. The 431st tangled with some Oscars and despite skillful enemy flying, shot down three, one falling to Mac McGuire. This was his twenty-first, making him the SWPA’s leading ace.

The next day, 28 July, the big fighters again cleared Mokmer by 0740, target Amboina, a small island off the southwest coast of Ceram. The B-25s of the 345th Bomb Group had already launched and the Lightnings easily caught them at the Mccluer Gulf, forming up into airborne legions as they swept past dead or dying enemy fields like Babo, Kokas, and the Sagans. As they passed on, the weather worsened until the Mitchell main force quit and turned for home.

MacDonald and Lindbergh, flying with the Possums, led two flights up to 18,000 feet and cleared the thunderheads. Unnoticed, Lieutenant Herbert W. "Herbie" Cochran's Lightning, number 186, was going down after first the right, then the left engine quit. Too low to bailout, Cochran successfully ditched in the sea. So quickly had the lieutenant gone in that later his wingman, Lieutenant Ethelbert B. "E. B." Roberts assumed the downed pilot had snafued and had gone back to Mokmer.

Floating in his emergency raft Cochran paddled about. Suddenly droning engines caught his attention, the 345th had aborted the mission and now flew directly overhead. Only then did he notice the open bomb bay doors. Unseen from above, a tiny figure furiously waved an oar. Cochran thought , "Don't drop those damn things here. You're gonna kill me." Suddenly the air filled with bombs which somehow all missed the lieutenant. Later Cochran paddled ashore and, still wet, was greeted by "What happened to you?" Usually a calm man, he blurted out " What happened? What happened! I darned near got killed, that's what happened!"

Blue and Yellow Flights of the 433rd, sans Cochran, broke free of the storm front and closed on Ceram Island. Moving south towards enemy fields the squadron swung into their loose, weaving formation and upped speed to the preferred 250 mph Approaching Amahai the cloud deck forced the squadron to just below the billowy white at 10,000 to 13,000 feet. Around 1000 the radio waves evidenced an unseen fight.

|

The enemy pilots were clearly veteran;. While Sonias shared basic characteristics of other Japanese craft- low wing loading and a high power to weight ratio- they were still two-place airplanes with fixed landing gear. And yet beset by the 9th's Lightnings they flew like demons stymieing "Captive's" best efforts.

MacDonald's flights traced the 9th's growing rage and frustration as the frantically twisting Japanese continued to evade their P-38s' gunfire. They listened anxiously to their radios, following the course of events as best they could:

"Damn ! I'm out of ammunition."

"The son of a bitch is making monkeys out of us. "

"I'm out of ammunition, too. "

MacDonald keyed his mike asking for the location of the fight, but the 9th grimly ignored the call; enemy craft were scarce enough without competition from Satan's Angel's. A 49er, Lieutenant Wade D. Lewis's cannon shells caught a Sonia in the left wing triggering a fire. As the enemy straightened out to run, Lieutenant J.C. Haslip finally slipped behind the green and brown mottled ship, fired a long burst drawing smoke, the stricken craft diving down into the sea. So died Sergeant Yokogi.

For thirty minutes Captain Shimada fought off Captive Squadron while MacDonald's flights frantically searched for the fight. Banking around a huge thunderhead, black flak drew the 475th to the long running battle three miles off Amahai drome. At 1045 drop tanks fluttered away as MacDonald led the flights into a turning dive from 3,000 feet, triggering a short burst that spangled the Mitsubishi with hits. It began to smoke. Trapped, Shimada decided to fight. Banking furiously, his wingtips streamed condensation as he wracked his craft around in a wicked left-hand turn. MacDonald's wingman and Group Operations Officer, Captain Danforth "Danny" Miller, tried pulling lead on the hostile fighter. Danforth caught it briefly in his sight's reticle and then lost the Sonia's track, his tracers falling off eighty feet behind. By then Shimada had completed his turn and dove on the next attacking Lightning lining up on the second element leader, Charles Lindbergh.

For all his experience the civilian had never seen, let alone fought, an enemy craft. Now he and Shimmed flew at each other head-on at 500 mph. Lindbergh instinctively sighted on the Mitsubishi is radial engine and held down the buttons, his fighter bucking, gunpowder fumes filling his cockpit. The civilian's bullets and shells, six seconds worth, slammed into the front of the Sonia, its propeller perceptibly slowing but still Shimada refused to break off. A moment before impact, Lindbergh pulled hard on the yoke vaulting Chimera’s ship by mere feet. As the stricken Mitsubishi poured smoke, it half rolled and took its last dive. Lieutenant Joseph E. "Fishkiller" Miller, Lindbergh's number two, snapped out rounds that took the Sonia in the wing, ripping off pieces. Shimada’s gallant fight ended in a spray of foam that briefly marked his passing. Years later MacDonald expressed admiration for that pilot who single-handedly outflown a squadron of P-38s only to be killed by Charles Lindbergh.

A grinning "Fishkiller" Miller, so named for his missed bombing strike that brought thousands of stunned fish to the surface, carried the word back to his comrades. Lindbergh scored his first kill "I was there, and the old man got a Sonia fair and square. . . . It really was something. I blew some pieces off the wing, but it was Mr. Lindbergh's victory." Congratulations flew through the camp.

Three days later, on I August, Lindbergh ventured out on a hazardous mission that almost proved his last. In a sense the affair happened because of boredom. Air activity had diminished and the pilots hungered for victories. Hades Squadron's Diary entry for July 1944 reflected a general frustration with the lack of combat. A mission on the twenty-seventh brought hostile contact and the squadron took on two Japanese fighters. Air discipline broke down and ". . . a general melee followed in which there occurred more danger from midair collision of friendly attacking aircraft than from enemy action. " It was from this hunger for victories that the Palau raid was born.

|

The colonel turned to Lindbergh. " You know, " he mused, ". . . with what you've taught us about fuel economy, we could go to Palau and stay at least an hour. " Lindbergh enthusiastically agreed. "Smitty " Smith broke in, reminding them of the morning's mission. Everyone forgot the suggestion, everyone but MacDonald.

The raid was postponed the next morning for an hour when F-5 "recco'' Lightning reported Ceram sealed in clouds. Half an hour later word came down, the mission had been scrubbed. MacDonald turned to Lindbergh, Smith, and Miller, "Do you want to go to Palau?" They agreed. At 0927 their Lightnings raised coral dust as they lifted free of Mokmer.

The northerly Palaus had been slated as a future invasion target but more than that, meteorological reports gave an atypical green light for passage to and from the target. Recent intelligence sightings estimated over 150 enemy craft secreted at various dromes, targets enough for all. And in a sense MacDonald also complimented Lindbergh by inviting him along. The four would make a 1,200-mile, over-water flight to an untested target. This would not be the usual "milkrun" mission reserved for beginners.

On the sweep north the civilian dove on a reef, clearing guns as he checked the boresighting on his borrowed Lightning. MacDonald, navigating skillfully with only a compass heading and a wristwatch, climbed to 8,000 feet and lit a cigarette, prepared for the long haul ahead. Despite frontal disturbances the flight crossed the southern portion of the islands, Peleliu, approximately two and one-half hours later. Climbing to 15,000 feet the marauding Lightnings skirted the eastern fringe of the islands as they moved north.

MacDonald was trying to pick off hostile craft in isolation but when none crossed his path the colonel decided "'to ring the doorbell." Slanting down into a fast, shallow dive, the four ships drew ack-ack fire over Koror Town hall-way up the island chain. Circling back to the coast they flew north to Babelthuap, the largest of the Palaus. Again crossing the surf divide they moved inland, now at combat speed, weaving through scattered clouds returning south. The Americans dived to the deck hunting the enemy. Skimming a lagoon they spotted several small boats and promptly strafed them.

Suddenly Meryl Smith radioed, "Bandits two o'clock high!"

Lindbergh's untrained eyes failed to see the pair of Zero floatplanes, "Rufes," that patrolled the far end of the convoy. Thus he later expressed some surprise when the lead elements drop tanks tumbled away. Following suit, he felt a slight bump as they cleared his ship. Instinctively hands reached out turning mixture full rich, brightening the gunsight light to compensate for the sun's glare, a glance showing 2,600 rpms and forty-five inches of manifold pressure.

Swinging starboard, the four Lightnings swept after one of the Mitsubishi’s low on the water. Lindbergh saw its partner to the left but held station, fully aware that the Palaus' overwhelming air defenses now knew that intruders threatened. MacDonald moved in behind the floatplane as it headed for the clouds, cut across its wild left bank and fired. The Rufe caught fire and a second later broke up on the sea's surface. Now freed from guarding the attacking element, Lindbergh radioed that he was going after the lone survivor. The last time he saw Smith, the major flew wing position but as the civilian made his final stalk an indistinct motion caught his eye to the left. Instinctively he turned to the threat and snap fired at too great a distance. It was Smith. Fortunately Lindbergh missed and dutifully lined up behind the major as the 475th pilot took the Rufe under fire.

MacDonald watched from above. Suddenly he noticed four, not three, craft above the water: the Mitsubishi, Smith's and Lindbergh's Lightnings, and a Japanese Hamp that simply materialized from above and behind. Before the C.O. could warn Lindbergh, Smith opened fire, bright motes of tracer bullets searching out, then catching the Rufe. It hit the water at a shallow angle, skipped, and then blew up as Smitty hit the fighter a second time. Firewalling his P-38, MacDonald warned Lindbergh, "Zero on your tail!"

Apparently Lindbergh either did not hear or misunderstood the warning because he never mentioned the event in his otherwise meticulously-kept journal. MacDonald dropped hard astern the Hamp. The Japanese, seeing him, pulled up into a sustained vertical climb that carried him to safety in some clouds. The time spent in combat, coupled with the hostile fighter, served notice that things would only worsen. The 475th's C.O. gathered the flight and withdrawing, spotted an enemy divebomber. With Smith and Lindbergh as high guard, he dove and sent the craft down in flames. After thirty minutes over the Palaus, MacDonald extracted the quartet of P-38s, taking advantage of cloud cover by flying east before resuming a course south to Biak.

Colonel MacDonald and Danny Miller led a mile ahead as the flight headed out to sea. Suddenly Lindbergh announced "Zero at six o'clock! Diving on us." A Zero plunged through a scattering of clouds curving towards Smith. Lindbergh responded too quickly, banking to intercept the bandit before the Japanese pilot had fully committed himself' to pursuing the major. lnstantly the Mitsubishi broke off its initial attack and cut inside Lindbergh’s turn, coining out on the American's tail.

The situation could not have been worse. The flight had retreated at a low altitude and the enemy had accrued a speed advantage through his dive. Lindhergh could not outclimb or outsprint the Zeke and help looked distant, MacDonald and Miller a mile ahead. Smith, still believing himself the target, climbing hard for the clouds.

http://www.mnhs.org |

MacDonald saw he was too late. Still far out of range he saw the Zero fire, delicate tendrils of tracers reaching out and enfolding Lindbergh’s fighter. Apparently, America had no monopoly on bad gunnery. Lindbergh's P-38 never faltered. lnstead it began a high speed turn, responding to MacDonald's call "Break right Break right!" Slowly the Lone Eagle led his pursuer in front of MacDonald's element, the colonel tightening his turn, ship groaning, buffeting, the tiny lighted "pipper'' in the sight sliding through the Japanese craft until proper lead had been established. Putt Putt Maru's gun package erupted bullets and shells; the Zero pulled hard for altitude. Smith flashed in for a quick shot, then Danny Miller, banking at the vertical, caught the climbing enemy with a full burst that drew plumes of black smoke. Critically low on fuel the flight left the crippled fighter and flew for home, landing at Mokmer at 1600.

Upon their arrival V Fighter Command summoned MacDonald on 2 August 1944, a day after Lindbergh almost died over the Palaus. Word of the mission had spread. Colonel Bob Morrissey, the civilian's contact at headquarters, phoned a day after MacDonald arrived. Unhappily he informed Lindbergh that the 475th's C.O. had been reprimanded and grounded for sixty days.

Most assumed MacDonald drew a reprimand for risking Lindbergh on a dangerous mission. While true MacDonald shouldered direct responsibility for Lindbergh's safety, one could argue that the free and easy liberties granted the civilian in both Marine and Army areas of operation lent an air of permissiveness to his stay. The extent of Lindbergh’s aerial involvement came clear two days before when he shot down a hostile craft, and yet no official prohibition surfaced then. The reasoning behind MacDonald's punishment further weakened in the following days. Lindbergh continued to fly combat. From 3 to 13 August he flew live operational missions that saw fighters, flak, and strafing runs. Not until the latter date did Kenney ground Lindbergh, by then on the verge of returning stateside.

Lindbergh, himself, suggested another reason for the V Fighter Command's peevishness:

It seems that the bombers have been requesting fighter cover for their Palau raid; for some time past and they have been turned down by Fighter Command on the grounds that the distance was too great and the weather too bad. Since our flight somewhat refutes this claim. Fighter Command feels that it has placed them in an embarrassing position, which they do not appreciate.

MacDonald had stumbled into a political tangle not of his own making and paid the price.

|

Just before departing for the U. S. Lindbergh flew a mission touched by tragedy. On the morning of 4 August the same day MacDonald began the first leg of his trip home, Lindbergh accompanied the 43lst on a bomber escort mission back to Amboina Island. Through a mix-up in signals the civilian lost contact with Hades Squadron, so he tacked on as a number four man to a flight of Lightnings. The target lay almost completely shrouded in overcast, strata pierced by spires of huge cumulus clouds.

Over Piroe Bay Lindbergh saw two bogies to the starboard. External fuel cells dropped away but as his flight wheeled to intercept, more than a dozen Lightnings converged on the enemy and a melee began. Captain Bill O'Brien, whose cool-headed leadership brought the 431st through "Black Sunday", spotted a Zero and dove for the kill. The enemy pilot spotted the approaching P-38 and pulled hard on the stick, attempting a loop either to come out on O'Brien's tail or, with half a roll at the top, to reverse his course and escape.

One or both pilots misjudged their actions. As the Zero went up, over, and straightened out, O'Brien flew head-on into the still inverted enemy fighter. Over a mile away Lindbergh saw a flash of light that meant only one thing, a midair collision. As the falling ball of flame burned out, thin black smoke rained fragments no larger than a Lightning's tail surface. Despite a search by the 431st the next day, O'Brien never returned and it was on that sad note that the civilian took leave of the group eight days later. Mr. Lindbergh was going home.

From the book "LIGHTNING STRIKES".

Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions | This site is not affiliated with the Lindbergh family,

Lindbergh Foundation, or any other organization or group.

This site owned and operated by the Spirit of St. Louis 2 Project.

Email: webmaster@charleslindbergh.com

® Copyright 2014 CharlesLindbergh.com®, All rights reserved.

Help support this site, order your www.Amazon.com materials through this link.