Aeronautical Genius, William Hawley Bowlus

Tubal Claude Ryan was a man on a mission. Desiring to become a flying officer in the US Army Air Service during World War I, in May 1917, he drove from San Diego to Venice, California to learn to fly. Here he met the man he would come to feel was an aeronautical genius, William Hawley Bowlus. The flight school in which both were enrolled was a rather less than reputable operation and were it not for the efforts of Bowlus repairing and maintaining the two aged aircraft, no one would have gotten any flight time.

Bowlus was a San Fernando Valley boy who had been building gliders of his own design since attending the 1910 Los Angeles Air Meet (first in the nation). He credited his experience with the gliders for, he said, his only needing an hour and a half of instruction to be able to fly power aircraft as well. At this time, Bowlus was on leave from the Air Service so that he could get his power license.

Left to right: Charles, Hawley, & Anne moving the Albatross at Mt. Soledad

|

Since he had not gone to college, Bowlus could not be an officer, but he did become a flight rated non-commissioned officer. As an aircraft mechanic and flying Sergeant at McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio, Bowlus would take part in some of the greatest aviation advances that occurred in the early 1920s.

After the war, Claude Ryan returned to San Diego and in 1922, began buying war surplus Jenny and Standard aircraft with the intention of converting and selling them in the civilian market. Realizing he could not do it alone, in 1924, Ryan sought out his old roommate from the fraudulent American School of Flight and Hawley Bowlus became the first employee of Ryan Airlines. Together they converted aircraft and even built the Ryan M-1 on their own when their aviation engineer cheated them on the design. They also began the first regularly scheduled airline in the United States, the Los Angeles-San Diego Air Line.

Ryan M-1 was a high-wing monoplane

The Ryan M-1 was a high-wing monoplane in a world of biplanes but went on to become popular with airmail pilots on the West Coast. The subsequent Ryan M-2 was an enclosed (cabin) version which airmail pilots really came to like as it got them out of the cold wind.

In the mean time, plans were made to build a larger version of the M-2, and Donald A. Hall, a recent graduate from the Pratt Institute, in New York, was hired to do the engineering. Dubbed the Ryan B-1 Brougham, it was intended that the first one would be sold to a local hotel owner, but when Frank Hawks expressed an interest, it became his.

Lindbergh, Bowlus connect glider controls.

|

Needing an infusion of cash, in 1926, Ryan sold half interest in Ryan Airlines to a flight student of his, Benjamin Franklin âBFâ Mahoney. It did not take long for Ryan and Mahoney to clash and Ryan sold out entirely to Mahoney later the same year.

Charles A. âLucky Lindyâ Lindbergh

Charles A. âLucky Lindyâ Lindberghhad been casting about for a trans-Atlantic plane for some time. He had gone to Giuseppe Bellanca but Bellanca would not build him the plane he wanted. Wright Aeronautical Corporation would not sell him a Wright Whirlwind powered Bellanca which they owned. Columbia Aircraft Corporation did manage to purchase the Wright powered Bellanca and agreed to sell it to him for $15,000, but with the requirement that they have their own crew make the flight. Travel Air would not even discuss the matter. At nearly $100,000, Anthony Fokker wanted way too much money.

The story was the same wherever he went. Lindbergh's St. Louis backers were firmly behind him and willing to meet almost any price--except Fokker's--but no one else would take a chance on him. After all, no one had ever heard of this skinny 25 year old kid who was more commonly known as "Slim" and who wanted to make such a dangerous flight. Although Slim Lindbergh had been a mail pilot and a barnstormer, and had three really spectacular plane crashes from which he got his "Lucky" nickname, he really had not made a name for himself.

Aviation History on the 3rd of February 1927

So, since no one else would deal with him fairly, a telegram eventually went out to San Diego's Ryan Airlines on the 3rd of February 1927, "CAN YOU CONSTRUCT WHIRLWIND ENGINE PLANE CAPABLE FLYING NONSTOP BETWEEN NEW YORK AND PARIS STOP IF SO PLEASE STATE COST AND DELIVERY DATE," and the rest is aviation history.

Serving as the Ryan Airlines Factory Manager under both owners, Hawley Bowlus was present the day in 1927 that the now famous telegram from the young, then unknown Minnesota mail pilot arrived in their San Diego office.

Lindbergh waiting for glider takeoff

|

Claude Ryan was in Los Angeles. He rushed back to San Diego.

BF Mahoney telegraphed back that they could build that plane, and at a bargain price of $6000 less engine and instruments—and that they could do it within three months! Eventually Mahoney would supply the engine and instrumentation at cost, hoping to make up any loss by the advertising bonus a successful trans-Atlantic flight would give Ryan Airlines. It was a big gamble for this virtually unknown airplane manufacturer.

The deal eventually came to $10,580 for a modified Ryan M-2 with a Wright J-5 Whirlwind engine, plus extras, at cost. Not only that, but Mahoney promised that they would do it in two months. With the Ryan crew and staff sometimes working 24 hours or more at a stretch, construction did actually take 60 days from when the order was placed on the 28th of February to the first test flight, on the 28th of April 1927.

Ryan NYP Spirit of St. Louis

The resulting trans-Atlantic airplane was the Ryan NYP Spirit of St. Louis.

Ryan said, "as factory manager, Hawley Bowlus was very much the driver—but he led, not pushed . . . . His drive was contagious and Lindbergh added greatly to the morale. It became a team." One member of the team would also become known for a solo trans-Atlantic flight of his own, former (Ryan) Los Angeles-San Diego Air Line's Los Angeles station manager, Douglas "Wrong Way" Corrigan. Another member was Bowlus' father, Charles ("CD"), who put in more time on the Ryan NYP than any two other Ryan employees. Under Hawley's leadership, much of the Spirit of St. Louis was built in advance of Don Hall's drawings.

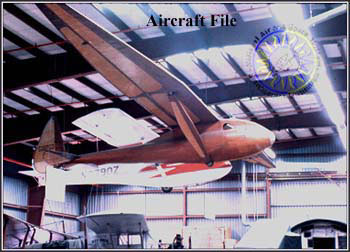

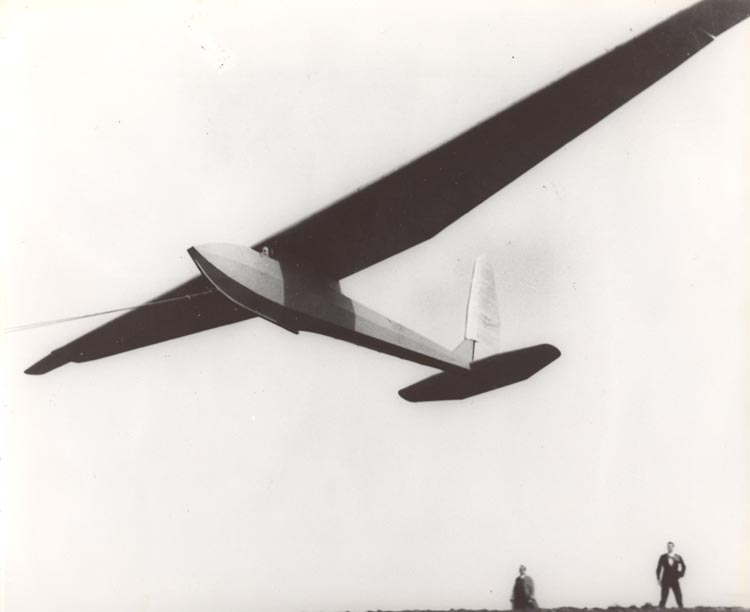

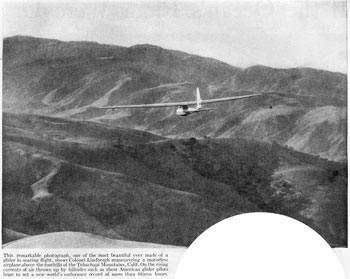

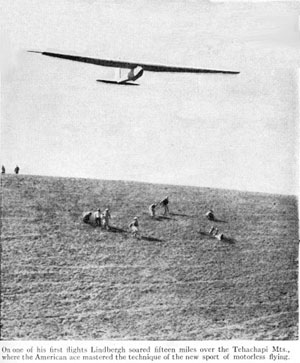

Lindbergh in flight over the Tehachapis. This remarkable photograph, one of the most beautiful ever made of a glider in soaring flight, shows Colonel Lindbergh maneuvering a motorless airplane above the foothills of the Tehachapi Mountains, Calif.

|

by Raul Blacksten

That year it must have seemed as if everyone and their uncle would attempt to be the first to make the New York to Paris flight. Commander Richard E. Byrd was to try it in a Fokker tri-plane, but Tony Fokker wrecked it on a test flight. Clarence D. Chamberlin, Columbia's chosen trans-Atlantic pilot collapsed the landing gear flying the same Wright-powered Bellanca that Lindbergh had originally wanted to purchase. Even less fortunate were Lieutenant Commander Noel Davis and Lieutenant Stanton H. Wooster, who were killed a few days before their scheduled attempt when their Keystone Pathfinder "American Legion" went down in a marsh. French pilots Captains Charles Nungesser and Françoise Coli flying their Levasseur White Bird were lost over Canada, never to be heard from again. It did not look promising.

Bowlus and Lindbergh became fast friends during construction. Later, Ryan Airlines sales manager A.J. Edwards would claim that Lindbergh stayed in his apartment during construction of the Spirit, yet Bowlus asserted that Lindbergh actually stayed with him and his wife, Inez, in their home on scenic Point Loma, outside San Diego.

Unfortunately, BF Mahoney may have become the poster boy for the old joke which goes:

Q: How do you make a small fortune in aviation?

A: Start with a large one.

Having trouble meeting his commitments for airplanes and paying his bills, Mahoney set about to re-capitalize what was by then called B.F. Mahoney Aircraft. Slightly more than six months after building the Spirit of St. Louis, a group of St. Louis businessmen bought the company, demanding 100% of the stock. They then promptly moved the renamed Mahoney-Ryan Aircraft Corp. to St. Louis.

The boost for which American motorless aviation had been waiting

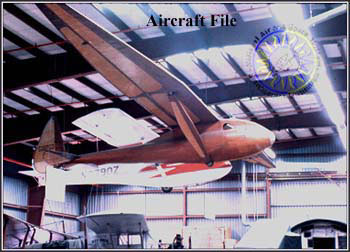

Bowlus-DuPont Albatross: Wingspan 18.8 m (61 ft 9 in),

Length 7.2 m (23 ft 7 in),

Height 1.6 m (5 ft 4 in),

Weight Empty, 153 kg (340 lb).

|

The effect of Lindbergh's flight to France was electric in the world of aviation. Droves of young people flocked to flying both power planes and the less expensive gliders. It was just the boost for which American motorless aviation had been waiting. Although gliding was an extremely popular activity in Europe, it had languished in the US but all that changed when Lindbergh landed in Paris.

Seemingly overnight, thousands of Americans flocked to flight schools, both power and glider. Responding to this surging demand, dozens of glider manufacturers cropped up, hundreds of glider clubs were founded, and numerous commercial glider schools established. JC Penny, Jr. founded the American Motorless Aviation Corp. in 1928 and invited various German glider pilots to set-up the first formal glider school in the US at Cape Cod. Also in 1928, Edward Evans founded the Evans Glider Club in Detroit and oversaw its conversion into the National Glider Association (NGA) in 1929. Although the NGA only lasted until 1931, out of its ashes arose the Soaring Society of America, now 70 years old.

When Mahoney-Ryan moved to St. Louis, Bowlus opted to stay in San Diego. In 1928 he began construction of his first successful state-of-the-art gliders which he called the Bowlus SP-1 Albatross, it was his 16th since 1911. With this and subsequent Albatross gliders,, Bowlus became the pre-eminent glider pilot in the United States and repeatedly set and broke his own records.

In 1929, he founded the Bowlus Sailplane Company, Ltd. and began manufacturing gliders in the same smelly old fish cannery in which the Spirit of St. Louis had been built. He also began training glider pilots. Nine of the first ten licensed glider pilots in the US were Bowlus students and flew Bowlus gliders.

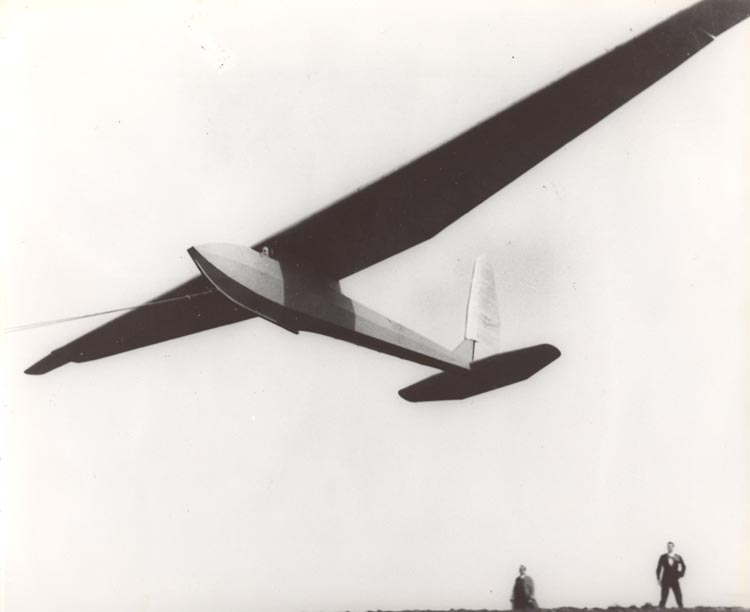

Bowlus and Lindbergh

It is clear that Bowlus and Lindbergh did make a friendship during construction of the Spirit because newlyweds Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh came back to San Diego three years later and looked-up Bowlus

Although he had already flown the Atlantic and had even flown a glider for a mile in St. Louis, Charles A. Lindbergh was not an expert glider pilot. So while in San Diego on their rather extended honeymoon trip to California, Lindbergh decided to fly gliders with his friend Hawley Bowlus. The Lindberghs also made several soaring expeditions with Bowlus and/or his gliders. The gliders which the Lindberghs flew in California were all designed and built by Bowlus.

Charles Lindbergh Soaring Over the Tehachapis

|

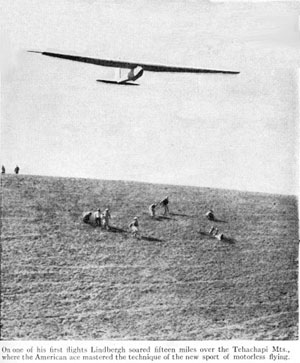

Lindbergh made his first glider flight in Bowlus' 18th glider, a Model A Albatross, on the 19th of January 1930. His instruction consisted solely of being told where the best lift would be found and that he should not bank the glider when turning so as to avoid losing altitude. Before 400 observers, Lindbergh soared Point Loma's Pacific Ocean face for a half an hour, cruising out over the Pacific almost half a mile, and gained five hundred feet above his launching point.

Charles A. Lindbergh earned his First Class Glider Pilotâs License, the 9th in the US to do so.

After soaring for the requisite time to obtain his license, he was asked if he was ready to land. He shouted down "I should say not. I'm having the time of my life." He later exclaimed, "that was the most stimulating air ride I've ever had and I'm going to do everything possible to speed the advancement of gliding. Isn't it strange that such a superlative sport has not come into more general use?" For this accomplishment, Charles A. Lindbergh earned his First Class Glider Pilot's License, the 9th in the US to do so.

After this flight, Lindbergh said, "Hawley, for a long time I have wanted to fly a glider, but have been waiting until I could fly one of yours."

Anne Morrow Lindbergh experienced her first glider flight and wrote about it to her mother:

âWe are back in Los Angeles after the most exciting day. Gliders! Elisabeth will appreciate that. Do you remember Con and I begged her to bring back a glider from Germany? C. [Charles Lindbergh] has a friend in San Diego, Hawley Bowlus, who has built what he calls a âsail plane.â It has a tremendous wing span and a small body (no engine, of course) and looks just like a great gullâperfectly beautiful . It has no wheels but just skids onto the ground, landing on its shiplike keel . . . Hawley Bowlus has painted the body (fuselage) a deep sea blue and the great tapering wings are silver.

âThe pilot sits in the front; there is only room for one, of course. Hawley is very interested in the project from the point of view of teaching young boys and girls to fly, as it is inexpensive to build, needs no gas, etc., to keep it up. Also, it is so much safer than power flying—slower, of course, and you land slowly and lightly in a few feet almost anywhere. And it is wonderful training for the prospective power pilot: knowledge of air currents, landings when his motor has failed. And it is such fun.

âC. went up in one a week ago and I wanted to try it. So yesterday I was towed behind a car across a field in a training glider. The car goes faster and faster, pulling the glider behind it, and you point the nose up a little, and up you go. Then they cut the rope loose and you glider down.

âI didnât make very good landings with this and bounced lightly like a balloon. It was terribly funny.â

In addition to building gliders, Bowlus had designed the Bowlus System of Glider and Sailplane Instruction. This consisted of a series of steps for the student to master before being allowed to actually fly a glider. The potential pilot would be towed on flat ground (Lindbergh Field in Anne's case) behind a roadster with their instructor shouting instructions in a megaphone and progress from a "Penguin" (a flightless bird), to a primary glider, before being allowed an actual sailplane flight. This system was remarkable because it was then common that the first flight a glider student took was also their first solo, often down the side of a hill. Anne Lindbergh went through the Bowlus system on "Galloping Gertie" the school's Bowlus primary glider.

Anne's Lindbergh solo

|

Anne Morrow Lindbergh became the first woman to earn a First Class Glider Pilotâs License

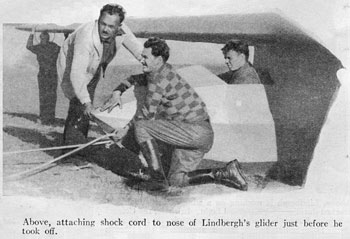

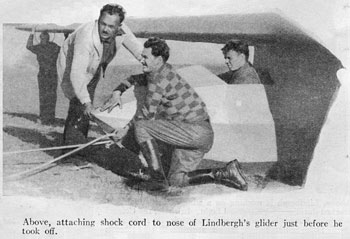

Inspired by her husband's enthusiasm for gliding, on the 29th of January, only a few hours after her first glider lesson, Anne Morrow Lindbergh became the first woman (and 10th person in the US) to earn a First Class Glider Pilot's License. She accomplished this with a brief flight in the same Bowlus Model A Albatross, clad in white coveralls and headband. Shock (bungee) cord launched from the 800 foot Mt. Soledad, near San Diego, she remained aloft for over six minutes and crossed the highway north of La Jolla twice before landing. Six minutes is not a long time but it was all that was required at the time to obtain a license.

This feat inspired the formation of the Anne Lindbergh Glider Club which was founded in San Diego to accommodate the distaff glider pilots who were encouraged by her exploits. Although it bore her name, there was no real connection between the club and its namesake.

On the 30th of January 1930, Lindbergh managed to coax another half hour flight out of a Bowlus Model A Albatross along Point Loma, flying up as far as La Jolla.

The Lindberghs then flew off to Los Angeles. A short while later, Charles Lindbergh flew back down to San Diego in order to pick-up Bowlus. Lindbergh wanted to scout the area north of Los Angeles in search of a suitable place to fly gliders and wanted Bowlus' expertise. They found what they were looking for in the Tehachapi Mountains that separate the San Fernando and San Joaquin Valleys. It was also near CD Bowlus' San Fernando Valley ranch.

Mr. & Mrs. Lindbergh and crew at Lebec base camp.

|

Soaring expedition near Lebec

The plan was to escape the reporters for a few days of carefree soaring. Therefore Bowlus, the Lindbergs, and a small crew made a soaring expedition near Lebec, at the southern end of California's San Joaquin Valley. There they hoped to soar along the western slope of the Tehachapi Mountains unnoticed. It did not quite work out as planned.

While at Lebec, they flew the same multiple record setting Model A Albatross that both Lindberghs had earlier flown. Weighing only 175 pounds, the Model A was state-of-the-art and was the most advanced glider series then built in the United States. It also sported wing tip ailerons. That is, instead of conventional trailing edge ailerons, the entire three feet of the wing tip rotated for roll control. This type of aileron is very efficient but it is also very prone to damage.

On the 3rd of February, after winning a flip of the coin for the first flight of the first day at Lebec, Bowlus drug a wing tip while landing and bent one of the aileron torque tubes. No problem, he thought after inspection, and he just bent it back into its proper position. Lindbergh next climbed into the glider and took off.

On the 7th floor of the Bullock's Department Store in downtown Los Angeles, Glenn Bowlus was displaying one of his brother's latest sailplanes. All at once, store personnel rushed to Glenn with the horrible news already being reported in the local newspapers, that a wing had come off Lindbergh's glider.

Lindbergh had crashed

Lindbergh on the Bowlus G-100 "Galloping Gertie" primary glider.

|

It seems that promptly upon Lindbergh being launched at Lebec, the formerly bent aileron fell off when the glider reached about 40 feet. It looked worse than it really was because due to the nature of wing tip ailerons, only one is needed to maintain control. Lindbergh continued to fly with no problems and landed safely near a schoolhouse (much to the delight of the teacher), about five miles from his take-off point.

Although they had tried to discretely escape the press and have a little fun, Bowlus, Lindbergh, and crew had made the mistake of stopping in a "Grapevine" area cafĂŠ for breakfast. Someone at the cafĂŠ recognized Lindbergh and alerted the press. It did not take long for dozens of reporters to find the glider pilots' encampment. When the aileron separated from the glider, the witnessing reporters rushed to the nearest telephone to report that Lindbergh had crashed.

The glider pilots of course knew better. Although only sixteen or seventeen years old Bud Perl was already an experienced glider pilot. He therefore calmly hooked the glider trailer up to the car and took off across the fields and down the dirt lanes after Lindbergh with Bowlus, William van Dusen, and a reporter riding shotgun. Five miles later, they found Lindbergh and the glider. "HE CRASHED" was the reporter's observation as he demanded that Perl take him back to a telephone—never mind that if he had crashed, Lindbergh would be needing help.

What they actually saw as they approached the landing site, was that while he awaited someone to come and get him, Lindbergh had disassembled the glider and pieces of it were lying about, complete and undamaged except for the missing aileron. Instead of looking for the nearest telephone, Perl, the reporter, and the others loaded the glider onto the trailer and returned to the encampment.

Lindbergh later reported that he had never been worried about being injured as the glider flew nearly as well with one wing tip aileron as it had with two.

Subsequently, another glider was brought up from San Diego while this one was repaired and the flying continued at Lebec for the rest of the week. When repairs were completed, Lindbergh insisted that he be allowed to do the test flight, and had a most pleasant experience.

Lindbergh was ecstatic and ordered an Albatross on the spot

Hawley Bowlus with his 16th, the Model SP-1 Albatross. This is similar to the one that the Lindbergs flew.

|

Thursday, the 6th of February dawned with frustratingly calm air. It was not until 4:40 pm before Lindbergh made the first flight of the day despite the lack of a ridge-soaring breeze. At first he found no lift and lost about half of his altitude. Suddenly, the Albatross' 62-foot wings came through some lift. Lindbergh banked into it and cored the thermal. Up he went and after nearly 20 minutes finally lost the lift. Although landing only five miles from his take-off point, he had covered fifteen. Lindbergh was ecstatic and ordered an Albatross on the spot.

Lindbergh told the press, "further soaring will probably be done in the San Diego area. We plan to carry on at Point Loma, due to the steadier winds necessary for endurance soaring. But we will still further explore California for promising soaring sites of the future."

After a week of flying at the base of the San Joaquin Valley, Bowlus and most of the rest had to return and tend to business in San Diego. The Lindberghs were under no such time restraint since they were on their honeymoon, which they resumed.

Before parting or shortly thereafter, indications are Lindbergh requested that Bowlus send him an Albatross to use in the Monterey Peninsula area. One way or another, an Albatross was unloaded from a ship at the Port of San Francisco on the 3rd of March 1930 and came to be promptly driven down the coast by Bowlus associate Jack Barstow. The glider and crew arrived in Pebble Beach a few hours after the Lindbergh's own 1:00 AM arrival.

After breakfast Lindbergh went down and examined the glider. To the press, he would repeatedly deny that he had any connection to the glider whatsoever. Nevertheless, once in Pebble Beach, the glider ended up being stored in a garage at the Del Monte Lodge where the Lindberghs (but not Barstow) just happened to be staying.

By no means admitting anything, he would later claim that he was just "experimenting" with the glider. It was, however, generally understood that he was hoping to fulfill part of Bowlus' lifelong unfulfilled dreams, that of flying a glider from San Francisco to Los Angeles.

The next morning, Lindbergh again examined the glider which was subsequently named "Anne Lindbergh." Taken out to Carmel and with a sealed barograph placed in the glider, Lindbergh fueled speculation that he was in the area to set records when he told members of his party to not worry if he failed to return for several hours. Briefly flying out over the ocean near the Carmel Highlands that afternoon, Lindbergh made a six minute flight before a large crowd of reporters, newsreel cameramen, and local residents. Yet for several days Lindbergh would continue to deny any desire to do anything but experiment.

There must have been a feeling of dèjå vu in the air on Saturday, the 8th of March. That day, Lindbergh was finally able to make a crowd pleasing seventy minute flight before a large assemblage. It was estimated that he even managed to gain 1000 to 1500 feet above take-off. A very successful flight by all accounts but as Lindbergh was coming in for a landing, his left wingtip aileron came off. As at Lebec a month earlier, although a dramatic occurrence, there was no serious problem and he landed safely.

In order to have the glider ready for the next day's flying. Lindbergh, Barstow, Bud Perl, and others worked half that night to repair the left aileron. No mention is made in the newspapers about whether or not Lindbergh may have drug a wingtip during that or an earlier flight but the conclusion was that the aluminum torque tube had suffered corrosion or possibly electrolysis. Just for added insurance, they decided to reinforce the right aileron as well.

One day, a primary glider arrived from San Diego. It was reported to have been a Curtiss training glider but it was probably another Bowlus. The appearance of this glider fueled more speculation as to what Lindbergh's intentions were and what he planned to do with the primary. As it turned out, the primary was for J. Cheever Cawdin, a business associate of Lindbergh's. Under Lindbergh's tutelage, Cawdin flew the primary on the Del Monte Lodge's polo field.

It must have been frustrating. So much effort for so little result. While looking for something to do during the obstinate non-soaring weather one day, Lindbergh borrowed Highway Patrolman Leo Ramsey's motorcycle and tore up the local roads.

More fruitless attempts at glider flying would also take place near Carmel at the ranch of Sidney Fish, where on the 11th the Lindberghs would also relocate. After one very brief flight at the Fish Ranch, Lindbergh barely missed hitting the telephone wires that lined a road. As reported in the local newspaper, "rather than being a narrow escape" it "merely evidenced a high degree of skill in manipulation of the controls and absolute confidence in his craft."

Unfortunately, during the Lindberghs' stay on the Monterey Peninsula, the weather just would not cooperate. Even an anticipated strong west wind resulting from a storm did not pan out. Except for that single seventy minute flight, not much was accomplished but it was not for want of trying.

Even if the press constantly speculated as to what he was up to, Lindbergh just as regularly denied that he was doing anything more than "experimenting." This way, at least Lindbergh had not said or done anything himself to raise the press' expectations. If he had ever admitted he was there to set records, and did not, the press would have had a field day. By keeping expectations low, he could not be criticized if he failed and could have reveled in the praise if he had done something noteworthy..

The reclusive Charles Lindbergh and Hawley Bowlus never got together again

At the conclusion of their California soaring exploits, the Lindberghs resumed their rather extended honeymoon. Although Lindbergh ordered a Bowlus Albatross, except for the one used in Monterey, there is no record that one was ever delivered to him and the Lindberghs are not known to have flown gliders again. The reclusive Charles Lindbergh and Hawley Bowlus never got together again. However, when Bowlus was severely injured in a glider accident at the September 1930 US National Glider Championships in Elmira, New York, Lindbergh did persistently press contest officials for a through report on Bowlus' condition.

Attaching shock cord to nose of Lindbergh's glider just before he took off

|

In the succeeding years, both men had some rough times but Bowlus came to be one of the most innovative and best known glider manufacturers in the United States. Up through the end of World War II, Bowlus' gliders and sailplanes were always cutting edge and even ahead of their time. He also developed and built the Bowlus Road Chief, which was America's first all-metal travel trailer, ultimately becoming the famous Airstream Trailer so well known today.

Hawley Bowlus died launching his boat at the Long Beach Marina on the 27th of August 1967. He was in the midst of building the prototype Lear Jet.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anonymous. "Charles Lindbergh's Glider Flight From the Sidney Fish Ranch, Carmel," Carmel Pine Cone, March 5, 1930.

Anonymous. Various articles, Monterey Peninsula Herald, March 4 to 15, 1930.

Benbough, Richard. On the Wings of an Albatross, the Story of William Hawley Bowlus, Richard Benbough, San Diego, 1977.

Bowlus, Glenn H. Unpublished letter to Ruth Bowlus. Undated.

Bowlus, Ruth. Unpublished interviews over several years. Undated

Lindbergh, Charles A. The Spirit of St. Louis, New York, Charles Schribnerâs Sons, 1953.

Lindbergh, Anne Morrow, Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York & London, 1973.

Meakin, Bob. âSpirit of Lebec,â Westways, 1974.

Perl, Adolph. Unpublished interview, 2 October 1999.

Schweizer, Paul A., Wings Like Eagles, Washington D. C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1988.

Teale, Edwin W., The Book of Gliders, E. P. Dutton, New York, 1930.

van Dusen, William. âCharlie Lindbergh Glider Pilot,â Western Flying, May 1930, pp. 50-53, 143.

Wagner, William. Ryan, the Aviator, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1971.

Walker, Donald F. Unpublished letter to Hawley Bowlus, 4 November 1930

Author-Raul Blacksten

Raul Blacksten is the Archivist for the Vintage Sailplane Association and edits its quarterly newsletter/magazine Bungee Cord. With a Master's Degree in history, he has had numerous articles on soaring and the history of soaring published on three continents. He is also in the midst of writing the biography of Hawley Bowlus. Raul can be contacted at: PO Box 307, Maywood, CA 90270 USA or raulb@earthlink.net.

© 2002, Raul Blacksten