Lindbergh & Conservation

By ALDEN WHITMAN When people of think of Lindbergh, they typically visualize a courageous young man flying alone from New York to Paris. In his later years, Charles became an active advocate of conservation, believing that the quality of life could only be preserved and improved through a successful balancing of technology and conservation. To this end, he endeavored to help indigenous tribes in the Philippines and Africa and campaigned to protect endangered species. The Charles A. Lindbergh Fund was founded in 1977 to honor not only Lindbergh the flyer, but the substantial contributions he made in the half-century after the flight in the fields ranging from aeronautic research and natural resource conservation to biomedical research, exploration, and wildlife preservation. Learn more >>>

MANILA - June 23, 1969 - Charles Augustus Lindbergh, whose life for the last 40 years has been devoted to aviation, has taken on a new role -- that of a passionate and articulate spokesman for conservation.

Profoundly convinced that civilization is imperiled by modern man's reckless disregard for important wildlife species, for primitive peoples, for irreplaceable timberlands and for unique marine life, he is spending a substantial part of his time and energies as a conservationist.

"We are in grave danger of losing forever not just millions of years of evolution on earth, but the eons of change that have produced man and his natural environment," he has said.

In the process of his involvement in conservation, Mr. Lindbergh has become willing -- "where I can accomplish a purpose" -- to lift briefly the cloak of inviolable privacy he has maintained since the kidnapping and murder of his first son, Charles Jr., in 1932.

The man who captured the world's imagination in 1927 by his solo flight from New York to Paris in the Spirit of St. Louis relaxed his privacy rule last month when he allowed a reported and a photographer to join him on a strenuous round of activities here. He did so because, as he put it, "the Philippines are one of the last frontiers of conservation" and because he felt he could spur its fledgling conservation effort. Mr. Lindbergh's concern with the Philippines is recent. His attention was drawn to the archipelago last year by Prof. Tom Harrison of Cornell, who alerted him to the plight of the Tamarau, a deer-like animal regarded as a national symbol and the monkey-eating eagle, reputedly the world's largest. Both are nearly extinct.

Mr. Lindbergh visited the islands briefly in January to scout the conservation situation, which also includes a threat to the survival of a number of aboriginal tribes, and returned in May for 12 days of vigorous conservation "campaigning." On this tripe he traveled thousands of miles, made scores of short pep speeches, shook at least 2,000 hands, ungrudgingly gave hundreds of autographs and even stood sponsor to a bridegroom at a tribal wedding at a cost of $8 -- all to put the weight of his personality and convictions behind private and public conservation ventures.

The trip was one aspect of his growing personal contribution to saving what he sees as man's priceless heritage. Over the last several years he has played a significant part in efforts to keep from extinction the blue and the humpback whale and the one-horned Javan rhinoceros.

He has joined in the task of preserving the wild animals of East Africa and the polar bear in Alaska. He had undertaken to focus attention on the perils to marine life in the Pacific Basin and elsewhere. Also he has campaigned for the setting aside of "core areas" of primeval forests and jungles throughout the world.

"I've had enough publicity for 15 lives"

Although the 67-year-old Mr. Lindbergh shuns public attention ("I've had enough publicity for 15 lives") he is perfectly aware that to many people he is a mythic figure, an authentic hero, for his epic trans-Atlantic flight 42 years ago, and that his views thus command special respect.

The public role is not easy because he has been reclusive for some 30 years -- since, in fact, his controversial involvement with the rightist American First Committee immediately before World War II.

He earns his living today -- as he has since his flight to Paris -- as an airline consultant, mostly for Pan American World Airways, of which he is also a director.

He lives inconspicuously with his wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, the writer, in a shorefront home on Long Island Sound. He has refused to be photographed or to appear on television. He takes pride in the fact that he travels economy class on a plane without being recognized; that he is just another traveler as he checks into lesser know hotels around the world, and that he walks the streets of New York as one of thousands of hurrying pedestrians.

By preference, too, he shops for his clothes anonymously and mostly in Army-Navy surplus stores; and while traveling he carries all his possessions in a single brown suitcase weighing less than 30 pounds that he tucks under his plane seat.

But for conservation's sake, he is willing to make speeches and to be presented as "General" (he is a brigadier general in the Army Reserve) rather than as "Mister" Lindbergh. Explaining his attitude, he said: "More and more, as civilization develops we find the primitive to be essential to us. We root into the primitive as a tree roots into the earth. If we cut off the roots, we lose the sap without which we can't progress or even survive. I don't believe our civilization can continue very long out of contact with the primitive.

"After all, the primitive developed life. Civilization must be based on life. We should never forget that human life was created in and for millions of centuries, was nourished by primitive wildness. We cannot separate ourselves from this ancestral background. It is folly to attempt to do so. I believe that many of the social troubles we face today result from our being already too far removed from our ancestral environment.

"People who have never had contact with nature are in a tragic situation, for they cannot realize what they have lost. When I live only in a city environment for many weeks, I don't feel as well mentally of physically. That is one of the reasons I like to visit the wilderness and sometimes its isolated tribes.

"Many people consider tribal groups primitive. Actually, these groups show the genetic defects caused by tens of thousands of years of the intellect's impact on our human species. Even in isolated tribes, the intellect has developed knowledge rather than wisdom so far as life's fundamental progress is concerned.

"The real source of wisdom lies in the wildness that created man and his awareness. Whatever the intellect has done thereafter is trivial by comparison -- possibly even detrimental to life's progress. "The wisdom of life is primarily instinctive. It is obvious in the successful selection, the beauty and the balance of wildness.

"It is most easily seen where man has not set foot, even tribal man. But although tribal groups are now separated by ages from primitive wildness, we can learn a great deal from them, for they are much closer to the primitive man than we. They can help us retain contact with the roots of life, to understand the values as well as the hazards of instinct.

"I think there is nothing more important for modern man than to merge his intellectual knowledge of science with the instinctive wisdom of wildness."

Mr. Lindbergh's conservation activity is organized in association for four groups; the World Wildlife Fund; the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and its Survival Service Commission; the Nature Conservancy, and the Oceanic Foundation. He is a director of both the International World Wildlife Fund, with offices in Switzerland, and its United States branch. He is a member of an advisory board of the Nature Conservancy and he performs specific missions for the Oceanic Foundation. Representing the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, he attended the last three meetings of the International Whaling Commission.

Beyond these organizational affiliations, he pursues conservation as a private person making use of a worldwide network of friendships that he has amassed in a lifetime in aviation. This network includes political leaders, business executives and men of science.

In talking to these friends, he insists he is not an expert on conservation ("I just tell them how important it is"). Yet his knowledge of the field is factual and detailed.

Although he has been an evangel of conservation for only the last five or six years, his interest in the field began in his boyhood. Recalling how this interest had matured over the years, he said in the course of a long monologue: "I was raised in central Minnesota, you know, where my father had lived as a child when the area was still a frontier and was being homesteaded. As a child I used to lie on his bed, and he'd tell me stories of the frontier days and of his own hunting exploits.

"One thing he told me about that made a deep impression was the abundance of game in those days -- in the eighteen-sixties and seventies and eighties. The sky, my father told me, was black with duck, and the forest abounded in deer and bear and other wildlife.

"In my childhood in the same area, there were no bear, no deer, seldom a duct and only an occasional partridge. I felt quite keenly the absence of wildlife, for I was envious of my father's association with such exciting game and of his adventures in hunting.

"Oddly, I remembered his stories about the skies being black with duck when I was flying over Nova Scotia in 1927 on my way to Paris. I was flying low because I had such a heavy load of fuel, and I could see hundreds, maybe thousands, of duck in the Nova Scotia sky.

"But even before that, when I was 14, we drove from Minnesota to California in a Saxon 6. The country was wide open, and I got a sense of the West without fences on that drive. And later, when I was barnstorming in the early nineteen-twenties -- you'd take anybody up for a ride for $5 -- the West was still fairly open.

"Later, though, after 1927, when I was laying out routes for what became Trans World Airlines, I was struck and depressed in flying over the West by seeing fences come in and the wilderness breaking up. I flew close to the ground then -- I sometimes chased wild horses with my plans -- and I could see how Ścivilization' was taking over the West.

"I also watched the retreat of the wilderness in Central and South America when I was laying out routes there for Pan Am in 1928 and Ś29 or so, and when I was flying in the Pacific in World War II.

Mr. Lindbergh remarked that after the war, when he was a consultant to the airlines, he had considered taking some part in conservation efforts, but that the spark was not provided until 1964, when he went on a safari in Kenya with Ian Grimwood, the chief game warden of Kenya. Later that year, writing of his experience, Mr. Lindbergh said: "Lying under an acacia tree with the sounds of the dawn around me, I realized more clearly facts that man should never overlook: that the construction of an airplane, for instance, is simple when compared to the evolutionary achievement of a bird; that airplanes depend upon an advanced civilization, and that where civilization is most advanced, few birds exist.

"I realized that if I had to choose, I would rather have birds than airplanes."

Traversing the East African gamelands with Mr. Grimwood, Mr. Lindbergh told his acquaintance, "I felt the miracle of life."

"We talked all one night at camp," he continued, "with the bugs all around, of the problems of Kenya and of the need for conservation support there to save the wildlife.

"I concluded that I ought to do something, and I thought I'd try a magazine article to start with, which I wrote later for Reader's Digest and which DeWitt Wallace, a friend of mine, published in July, 1964.

"And when I got back to the States, I saw an article in The New York Times about the World Wildlife Fund. When I couldn't find the organization in the phone book, I called the New York Zoological Society -- I'm a member there -- and they steered me to Dr. Ira Gabrielson in Washington, head of the Wildlife Management Institute and the grand old man of conservation.

"He had taken on the presidency of the United States branch of the World Wildlife Fund, and they were just getting underway. I made a small contribution, and later I joined the board and then the executive committee.

"So, since then I've been trying to build up conservation interest all over the world, which I'm in a good position to do because, as a consultant to Pan Am, I travel a great deal.

"In 1965, I think, I joined the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, a scientific group, and as its representative I attended my first Whaling Commission meeting in 1966, where I learned of the danger to the blue and the humpback whale.

"Well, I love to go on expeditions with friends, and after the Whaling Commission meeting I was in the Peruvian Andes with a friend, and we were invited to the Presidential Palace. At lunch I talked with President Fernando Belaunde Terry about vicuna and about blue and humpback whales, which were then being constantly harpooned by hunters from a land station on the West Coast of Peru.

"Through the President, we were able to go out on a whaler and watch the operation. I found out that the Peruvian whaling company was controlled by a Minneapolis concern. The chairman of the board turned out to be a fellow Scandinavian, and I wrote him a letter outlining our reasons for wanting a ban on the uncontrolled harpooning of these endangered whales: the kill rate was above the reproduction rate.

"Ultimately, after consulting with his boar, he agreed with me, so the President of Peru was able to put into effect a voluntary ban on harpooning. This was a major step in saving the blue and the humpback whale. I think they'll come back now, that the herds will increase.

"I've been active, too, in Indonesia. I've been there twice, first in 1967, in an effort to deal with the critical situation of one-horned Javan rhinoceros. There are only a few of them left in Udjung Kulon, their only habitat, because they are widely hunted for their horns. It is widely believed in Asia that powdered horn from this rhinoceros will surely restore a man's virility, and this superstition is enough to have reduced the herd to between 20 and 25.

" I visited the Udjung Kulon -- I never did see a rhino, though -- and was able to understand the problems of guarding the rhino preserve from poachers. Now, after talking to Indonesian officials who want to save the animal and with some help from the World Wildlife Fund, I think we've got the problem of guarding the remaining rhinos from hunters in hand.

"Right now, I'm interested in preserving the coral formation's of the equatorial Pacific, which are endangered by scuba divers hunting commercially for souvenirs and potential jewelry and by dynamite fishing.

"It's time, I think, to set up marine reserves. It can be done very cheaply at this time, and often by executive proclamation. The problem is guarding the underwater areas. I've talked to the Governor of Hawaii, and I think there's a good chance we can get 1,200 miles of coral reef set aside as a park. It could be one of the world's great reserves."

Many Filipinos meeting him for the first time could not believe that he was the father of three sons, (Jon, Land and Scott) and of two daughters (Anne and Reeve) and that he had nine grandchildren. He put as much of himself into a chat with a pre-Stone Age tribesman as with a worldly investment banker.

"Hello, I'm glad to meet you," he said over and over, offering a large, freckled hand and at the same time extending his right leg and bending his knees so as to shrink his 6 foot-2 _-inch frame to accommodate the smaller statured Filipinos.

In the Philippines he worked mostly with three conservation leaders -- Sixto K. Roxas 3d, president of Bancom Development Corporation; Manuel Elizalde Jr., Presidential Assistant on National Minorities; and Jesus Alvarez Jr., officer in charge of the Parks and Wildlife Office. These men, with the encouragement of President Marcos, have since the first of the year set in motion a number of private and public conservation programs involving scores of influential Filipinos.

In his appeals to these man and women, the stress was on enlightened self-interest. Mr. Lindbergh took care to explain that he was not opposed to reasonable hunting, to reasonable lumbering, to reasonable commercial exploitation of natural resources.

"And of course, I'm interested in the Philippines. I think there's a unique chance here, given the combination of flora and fauna that can be saved and the apparent dedication of leading Filipino's to conservation."

To further the Philippines programs and to increase his own knowledge of the archipelago's wildlife and tribal minorities, Mr. Lindbergh arrived in Manila on May 8, and then broke dozens of business appointment's in other parts of the world to prolong his stay for 12 days.

In that time, he participated, with President Ferdinand E. Marcos, in dedicating a marker for a national sanctuary for the tamarua (Anoa mindorensis) of which only about 100 head remain. He also traveled to Mindanao Island to visit a project designed to help the aboriginal Mansaka survive, and to see the nesting grounds of the monkey-eating eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyl), now down to between 30 and 40 pairs because it is hunted for its plumage and for stuffing.

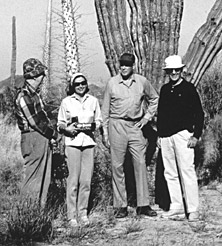

Speaking to groups, Mr. Lindbergh was an Impressive figure. Tall and erect but more stocky than when his nickname was "Slim," he looked younger than his years. Although his hairline is receding and his white-gray hair, parted on the left, is combed over a bald spot, his probing blue eyes and his ready smile convey an impression of youthful vibrancy.

On his field trips to remote jungle areas, he as an eager, alert, inquisitive searcher for new knowledge. He traveled by helicopter, plane, jeep and on foot; slept in the open using a shoe for a pillow and a light nylon raincoat for a blanket; ate wild boar with gusto; drank fresh coconut milk and savored wild fruits with zest. He was up before dawn and to bed late. He neither smokes nor drinks -- not even cola beverages.

On one trip - to visit the aboriginal Batangan on Mindoro -- Mr. Lindbergh, a guide and two tenderfoot companions struck out over a mountainous trail for a tribal village. Skipping lithely over rock-strewn streams and bounding up slippery slopes, he reached the village well in advance of the rest of the party. Sweat-soaked clothes were the only sign of his exertion.

After shaking hands all around with the diminutive tribesman in their loincloths, Mr. Lindbergh popped questions at the headman, using an interpreter. Where did his people get their cloth? (Some was beaten out of bark, some bartered for sweet potatoes.) What did they eat? (Sweet potatoes, a little upland rice and wild pig they speared or trapped.) How long did it take them to construct their bamboo huts? (A day at most.) How did they till the fields? (With a pointed bamboo stick.) How did they plant? (The man digs the hole, the woman plants the seed.) How did they treat disease? (By a healing rite called "daanama," in which the healer -- "daanaman" -- exorcises the patient's evil spirits.)

After more than an hour of conversation and inspection of Batangan houses, fields and implements, Mr. Lindbergh shook hands again and loped back through the jungle to his helicopter.

On another trip, this one to the Batak people on Palawan Island, he explored bamboo houses and acquired an intimate knowledge of the people's life, habits and problems, including their marriage and burial rites.

Indeed, he was invited by a canny bridegroom to be a member of a wedding. In Batak practice, the ceremony is brief and to the point, consisting largely of the bridegroom's public payment to the bride of the bride price. This is an ascending amount, which depends on the number of times the bride had been married. In this wedding, the 15-year-old bride had been married once, and here bride price should have been 10 pesos. But in the general's honor, the amount was raised to 30 pesos, which he cheerfully supplied after borrowing money the money from Mr. Elizalde.

As part of the trip to Palawan, Mr. Lindbergh traveled by jeep and foot to an enormous limestone cave in the jungle to meet a group of Tagbanwa tribesman, who live nearby. These aborigines, more advanced than either the Batangan or the Batak, have a written language with an Indic script. In it their chief had inscribed a message to Mr. Lindbergh on wood and with a ball-point pen. It read:

" We understand that you are a good airplane pilot. We are grateful that you are able to visit our island at Palawan. We would appreciate it if you could teach us to fly, so we could visit your island some day."

Reprinted from the June 23, 1969 New York Times

http://www.oceanoasis.org

Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions | This site is not affiliated with the Lindbergh family,

Lindbergh Foundation, or any other organization or group.

This site owned and operated by the Spirit of St. Louis 2 Project.

Email: webmaster@charleslindbergh.com

® Copyright 2014 CharlesLindbergh.com®, All rights reserved.

Help support this site, order your www.Amazon.com materials through this link.